Weights or running? What exercise type are you?

We can’t blame our genes when our chosen workouts fail to produce the results we are after.

If you are gearing up for a return to the gym, it might be worth trying something completely different, particularly if your previous fitness efforts have floundered.

What makes workouts work for some people and not for others was the subject of a groundbreaking new study, published in The Journal of Physiology, in which a team of researchers from the University of Western Australia and the University of Melbourne found that we can all get fitter and leaner, and that there is an ideal exercise for everyone, but — and here’s the big surprise — our genes play less of a role than was previously thought.

For a decade or more, many exercise scientists believed that our aptitude for running or cycling, yoga or weight training, was written within our DNA. According to these theories, some of us were genetic non-responders to aerobic exercise, while others were programmed to respond poorly to strength training.

It provided the perfect excuse to ditch running or weight training when improvements seemed tediously slow. And it produced a booming market for DNA home-testing kits that promise to predict genetically matched personalised fitness plans. However, this latest study on twins, selected because they offer direct genetic comparison, found that we can’t blame our genes when our chosen workouts fail to produce the results we are after.

Daniel Green, a professor in cardiovascular exercise physiology at UWA, and the doctoral researchers Hannah Thomas and Channa Marsh recruited 42 sets of twins — a mix of male and female, with 30 pairs identical and 12 non-identical — all of whom were young and healthy, but non-exercisers at the start of the trial.

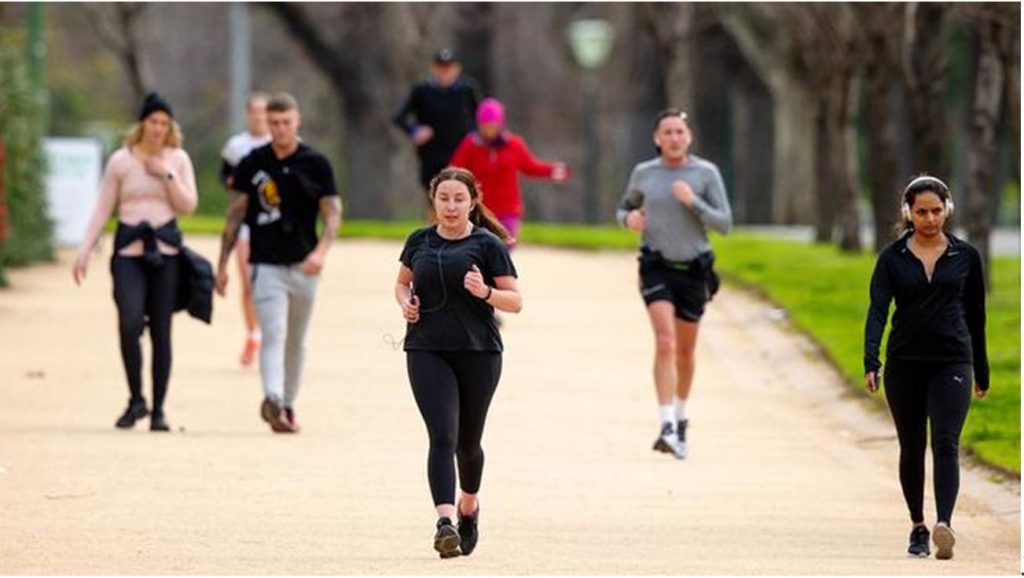

Australian research on twins found the results of exercise varied considerably.

For two three-month periods the twins were asked to exercise in their pairs, completing 60 minutes of running or cycling three times a week for one of the 12-week programs, then thrice-weekly weight training for an hour during the other 12-week slot.

After each three months of exercise prescription, Green and his colleagues tested for improvements in aerobic capacity, power and strength, comparing results with each person’s starting point as well as with the results obtained from their twin.

If genes underpinned fitness gains, their results would be similar, yet the data showed a mixed bag of reactions. Almost everyone got fitter, but even within twin pairs the responses varied considerably.

“We found little evidence that changes with training were primarily genetically determined,” Green says. “Our data suggests that, while genes contribute somewhat to the ‘size of your engine’, your ability to ‘tune it up’ — that is to enhance your fitness or strength — is mostly down to environmental factors.”

In other words, Green says, it’s not who or what you are that matters if you want to get fitter, leaner and more toned, but which workout you select and how else you live your life.

Other researchers are taking the findings seriously and asking, if it’s not genes, what is it that makes us respond differently to the same dose of exercise?

“For many years it was thought that our genes play a central role in how we respond and adapt to exercise, but this latest study suggests that our DNA probably doesn’t limit us as much as we previously thought,” says Dr Richard Blagrove, a lecturer in physiology at Loughborough University.

“It is likely to be lifestyle and other personal factors, such as diet, psychological state, body weight and previous exercise history, that have a larger bearing on the outcomes of our workouts.”

Of course, the million-dollar question is how do we know which workout will transform us from fatty to fitty? In his study Green found that roughly 30 to 50 per cent of people responded positively to both the weights and cardio exercises. There were a few wayward low responders who didn’t improve much with either approach, but even that could be down to the approach taken.

“There wasn’t a great deal of variation in sets, repetitions, recoveries, exercises, training frequency or exercise intensity,” Blagrove says. “So those who were deemed ‘non-responders’ to aerobic training might actually find they would have responded to a different style of aerobic training, such as adding some intervals or sprints.”

Green says many people will find that they do get fitter once they ramp things up. “Increasing the intensity of training can move the dial and produce greater benefit in those who are low responders to standardised prescriptions,” he says.

People prefer exercising, and perform better at it, in the middle of the afternoon — when they have eaten a couple of meals.

However, what you eat can also play a role. “It’s no coincidence that studies show people prefer exercising, and perform better at it, in the middle of the afternoon,” says Professor Jim McKenna, the head of the Active Lifestyles Research Centre at the Carnegie Faculty of Leeds Beckett University. “Part of the reason is that they are well fuelled, having eaten a couple of meals by then, compared with a pre-breakfast workout, when energy levels would be low after an overnight fast.”

Ultimately, there is no magic bullet (or expensive testing kit) that will find what works for you — it comes down to basic trial and error.

“All of those who failed to respond to one form of training in the trial were capable of gaining benefit by switching to the other,” he says. “Switching from endurance training, if that’s not working for you, to strength training might have some benefit.”

His next studies will attempt to look into a greater variety of exercise as well as the factors that influence fitness. One, he suspects, is mindset.

“An exercise form that people enjoy most they will adhere to for longest,” he says. “I was a sprinter and field hockey striker in bygone days who always struggled to run the requisite warm-up laps at training. Choose something you enjoy.”

People are less likely to stick with a form of exercise if they are not enjoying it.

HOW TO AVOID WORKOUT FAILURE

1. Do different workouts each month

It might be worth switching the focus to a greater variety of exercise, according to a study published in the journal Translational Medicine in January.

Dr Susan Malone, a researcher at New York University’s Rory Meyers College of Nursing, and her team analysed the exercise habits of more than 9000 adults who had completed the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Malone found that the greater variety of exercise people did, the more activity they achieved. And those who tried three different activities a month were the most likely to hit their 150-minute weekly target. “If we refocus people to more varieties of exercise, they might have more success reaching targets,” Malone says.

Joggers at The Tan, a popular Melbourne running spot, this week. Picture: Mark Stewart

2. Go easy on yourself

McKenna says we often make the mistake of selecting a class because it is fashionable or tough. “If exercise feels like a form of punishment, then it has drop-out written all over it,” he says. “Studies on emotional forecasting have shown that positive emotions to an experience are short-term, whereas negative emotions have a darker side and linger for longer.

“If you really don’t enjoy a workout there will be emotional and biological signals to avoid it. If something feels easy the first time you do it, that is a good sign, so stick with it and progress.”

The principal role of dopamine, the so-called happy hormone released by the brain after exercise, is to prompt us to find where to get it again. “Our brains and bodies will want to keep doing activities that we enjoy,” McKenna says. “If something is easy to start, then it’s hard to stop.”

If your exercise routine has been interrupted by the pandemic, treat it as a chance to reboot motivation

3. Embrace the fresh start effect

Whether your fitness soared or plummeted during lockdown, you should welcome what McKenna calls the “next new’‘ phase as a chance to reboot motivation. “For some people lockdown simplified daily life to make home workouts more accessible and easier to stick to,” he says. “Now we’ll all have to revert to relying on the complicated decision-making that used to make exercise so challenging: the planning of gym classes, packing kit, driving to the gym, showering, and so on.” Yet the prospect of starting over can be a positive motivator — use it as you would the new year to make changes for the better.

Stick with your workout for at least three months.

4. Don’t quit too soon

Even if you feel that one type of workout is getting you nowhere, stick with it for three months. “It would certainly be foolish to do a program of aerobic or strength training for a few weeks and then decide to give up because you aren’t getting the results you hoped for,” Blagrove says. “Some people will improve very quickly to a given dosage of exercise, but others may need slightly longer or a different approach to get the same results.”

5. Embrace your weaknesses

If you favour one type of exercise because you respond quickly to it and enjoy it, don’t neglect others. “It is important to remember that both aerobic training and strength training exercise are beneficial for everybody’s health,” Blagrove says. “Most of the participants in this latest study by Green did improve — and, in fact, 100 per cent of participants improved by various amounts following the resistance training.” The bottom line? Vary the ratio, but try to get a bit of everything in.

The Times

Get A Gym Membership Today.

Call now, we’d love to welcome you to our Southport Gym.